One of the struggles writers have is how to structure a chapter and how long a chapter should be.

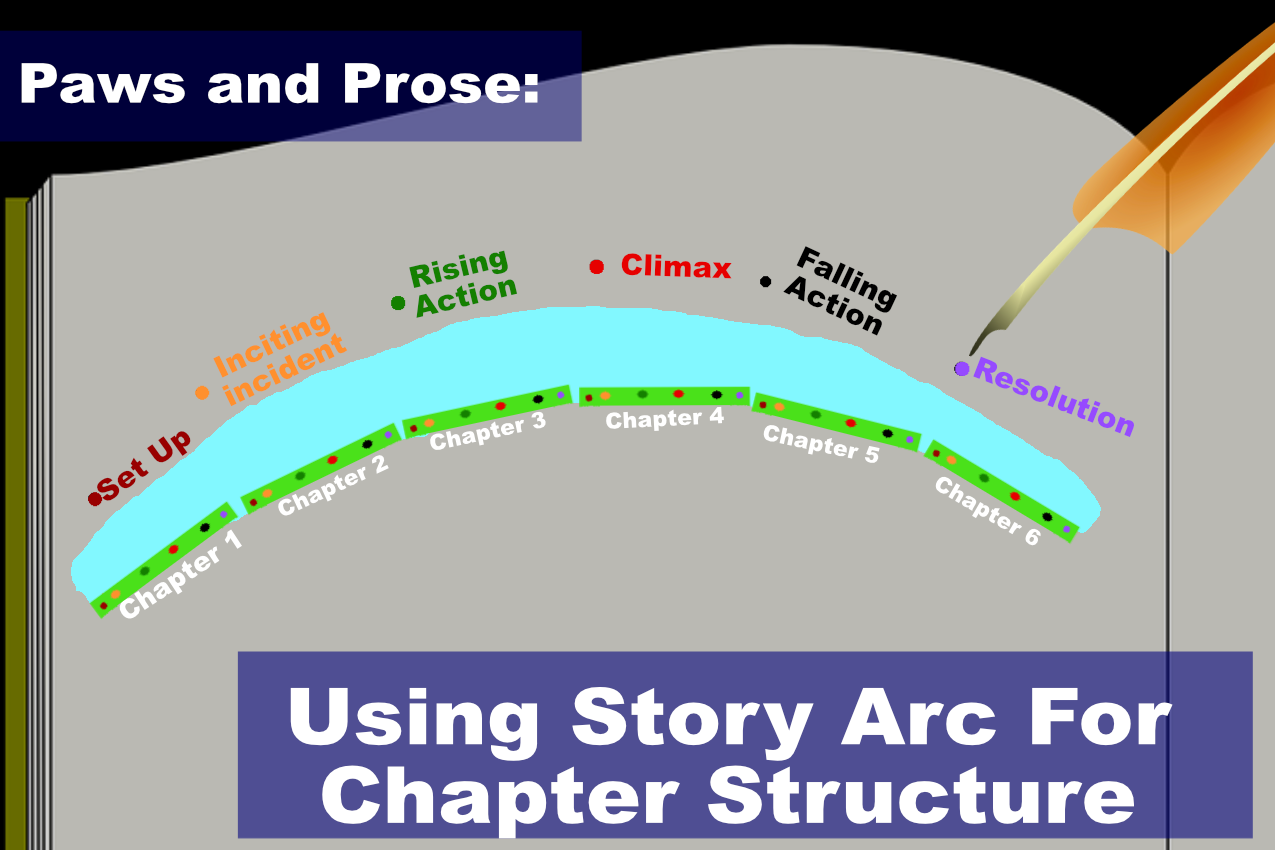

You may not be familiar with the narrative story arc, I’ll write a more in-depth post about that soon. Usually, the arc is referred to as a whole. That is, it’s only applied to the whole book, and not chapter by chapter. It’s important to see the story arc as part of the whole book and make sure you are hitting all key points, but I also feel it is important to see each chapter as a mini episode. This will help you with your chapter structure. One way to do this is by approaching each chapter as if it’s an individual story. Below, I’ll summarise the points of the Story Arc and give examples from chapters in Harry Potter and the Philosopher Stone so that you can see the chapter structure in action.

I have chosen Harry Potter and the Philosopher Stone because the chapter structure is simple to look at and is a widely known story.

Set-Up: Building to Events

Owls in daylight and a cat reading a map in Harry Potter and the Philosopher Stone: The Boy Who Lived tells the reader it’s fantasy. Characters are introduced. We know that the Dursleys have a snobbish attitude. This is part of the set-up for the first chapter.

Future chapters, the set-up point is the chapter before it. The Boy Who Lived showed us that Harry is magic and living with people who are not so this does not need to be set up in The Vanishing Glass. The story arc for chapter two can begin with Dudley’s birthday and the inciting incident.

The Vanishing Glass denouement sets up chapter three with Harry locked in the cupboard, awaiting his freedom (which will come and fail in the form of letters, then later will be successfully rescued by a half-giant).

The Inciting Incident: Something Happens to Call For Action

The inciting incident is an event that causes something to happen. In the overall narrative of Harry Potter and the Philosopher Stone, this is when the letters arrive. The action taken by the Dursleys is to flee. But the letters do not arrive until Chapter Three. So the inciting incident is different for each individual chapter.

The Boy Who Lived inciting incident is the mention of the Potters and the owls flying around during the day, as well as Vernon seeing—what appears to be a cat—read. This gets dialogue going between the Dursleys prior to Harry’s arrival, an action that makes the Dursleys uncomfortable. The inciting incident for The Vanishing Glass is Mrs Figg breaking her leg, leaving Harry without a babysitter. The Dursleys must take him to the zoo.

It is an important point for chapter structure as it prevents characters from becoming passive.

Rising Action: Tensions Arises

Sometimes this can be linked to the inciting incident or another step. It’s where the tensions have changed. It leads to the climax. For the whole narrative, this would be Chapters 6-13 where Harry makes friends and enemies, as well as learns about the world. But each individual chapter would have their own rising action.

The Boy Who Lived – Vernon is concerned with the owls and cloaked people that he must speak with his wife on a subject they have promised never to talk about.

In The Vanishing Glass, there are two scenes that could be described as rising actions but I think it’s more of a long rising action joined together with description. It starts with the realisation that Harry is coming to the zoo. Dudley is ‘upset’ but this time does not get his way. The Dursleys are afraid because of Harry’s past, where Harry has ended up on the roof, had his hair regrow, or shrunk clothes. They do not want any unexplainable events at the zoo. In the reptile house, Dudley and Vernon fail to get the snake’s attention but it notices Harry. The unexplainable event that Vernon and Petunia didn’t want was starting to happen. Harry has a full conversation with the snake. Tensions rise when Dudley notices the snake responding to Harry and pushes Harry aside.

As it leads to the climax, it is another important point for chapter structure. Some, like The Boy Who Lived, will be short. Others, like The Vanishing Glass, will be long.

Climax: The Twist and Turns

The climax is the highest tension within the narrative. For Harry Potter and the Philosopher Stone this is chapters 15-17 where Harry and his friends decide to go save the stone.

In first drafts, new novelists tend to break the chapter here. I do not recommend this, it’s more your midpoint. Or just after the midpoint. The bit that is making the reader want to know more. The Boy Who Lived has a long climax, some may be shorter. In The Boy Who Lived it is when a strange man comes to the street and removes all the light. A cat turns into a woman and they discuss the arrival of a baby with a man only the wizard trusts.

The reader wants more. They want to know what war, what baby. Why does the woman worry about the man yet to come. Imagine if Rowling ended the chapter before the baby came, it just wouldn’t have the same feel.

In The Vanishing Glass, Harry accidentally makes the glass vanish when Dudley pushes him aside. This is the twist. The surprise and the turn of events. Until this point, Vernon and Petunia had almost forgotten Harry was with them but the glass vanishing, and Dudley’s friend informing them of the conversation confirmed their fears.

Breaking too early could break your chapter structure, so make sure not to break until after the chapter climax.

Obstacle Outcome

This sits somewhere between the end of Rising Action and the start of Falling Action. It’s the bit where the focalised characters succeed or fail the obstacles that they face. Throughout the narrative, there will be more than one obstacle outcome, with different success levels.

- Harry fails to get a letter

- Hagrid successfully rescued Harry;

- Harry successfully gets to Hogwarts;

- The Golden Trio successfully wonder the castle at night (but meet fang).

- Harry and Ron successfully defeat a troll;

- Harry successfully gets the snitch;

- The Golden Trio unsuccessfully meet Hagrid at night

- Harry is successfully rescued at the forest;

- Harry successfully defeats Voldemort.

At a chapter level, you can look deeper. For Vernon in The Boy Who Lived, he failed. His obstacle was to address the events of the day, and although he attempted to do this, it left him feeling uneasy and uncertain that he didn’t approach it again. For Harry in the Vanishing Glass, the outcome was also a failure. He unknowingly used magic which got him sent to his cupboard under the stairs.

When looking at chapters, look at how many success and failures that the focalised characters have. Do not feel it needs to switch each chapter. Harry Potter’s first success is Chapter 4: Keeper of Keys, which is the third chapter where he is the focus of the narrative. Each narrative will have several turning points that will change the success rate of your characters.

Falling Action: After the Storm

After the climax, you have the falling action. Tensions ease and consequences of the events before come to play. Sometimes the obstacle outcome falls into here, as it does with the Vanishing Glass. Harry is kept under the cupboard until summer.

Other times, it is something new, like The Boy Who Lived. McGonagall’s acceptance that Harry should be away from wizarding kind and Hagrid’s arrival is the falling action.

Denouement: Closing the Chapter

The denouement of the chapter is it’s ending. As the chapters are mini episodes of a book, and not the whole thing, they should show that more is to come. For this, I think that the falling action does not fall all the way by the end of the chapter, but some tension remains.

The Boy Who Lived shows the reader what kind of people Harry will be living with, the reader will want to know he is alright, but they will also want to know what kind of boy he will be if he comes from a world of flying bikes and shapeshifters. The chapter stops with questions for the reader which draws them in and leaving the wanting answers, while also making them care about the characters they just met.

The same is applied to The Vanishing Glass. Readers want to know how Harry copes with being locked in his cupboard, when he is going to get out, and they empathise with his feeling of being alone and disliked at school.

Story Arc Conclusion

Although the story arc is often used to tell a narrative of a whole book, use it to tell each individual chapter as well. By having these points down as the bones (or frame) for your narrative, you are more likely able to determine the correct chapter structure and prevent yourself from ending the chapter too soon.

Some of the points (like inciting incident and rising action) may be the same and can therefore be combined. Other points will be separate but what’s important is that the chapter doesn’t feel like it’s missing something or that it ends at the start of the climax.

Like a story, treat a chapter like it has a beginning, a middle and an end. If you treat each one as a short or an episode, you’ll be on your way to having good chapter structure.

This is the same irregardless of genre, fiction or non-fiction. With my PhD, I try to give my academic chapters the same sort of feel.